The importance of truth on the road to reconciliation

Below, the incredibly gifted Yukon Tlingit artist, dancer, and lifelong learner Guná Jensen shares about her culture, artistic journey, and the incredible design featured on this year’s Orange Shirt from Northwestel. She also discusses the fundamental role of pursuing truth on the road to reconciliation.

If you find yourself lucky enough to meet Guná Jensen, her passion and enthusiasm for creative pursuits will be immediately apparent.

“I think I’ve always been a person who’s inclined towards the arts—I’ve just always had that creative spirit,” Guná tells us in mid-September, speaking with Northwestel’s communications team from New Denver, British Columbia, where she is an artist in residence at the Aunte Indigenous Residency with White Otter Design Co.

Chat with her a little more, and you’ll quickly discover that her artistic journey is closely connected with her cultural identity and that a passion for the arts runs deeply in her family.

Guná painting at White Otter Design Co.

Culture, family, and dance

Hailing from Carcross, Yukon, Guná is of Dakhká Tlingit and Tagish Khwáan Ancestry from the Dahk’laweidi Clan, which falls under the wolf/eagle moiety. For many generations, her family has called the Southern Lakes region of the Yukon their home.

“From when I was young, I was introduced to the cultural practices of my community, the Carcross/Tagish First Nation. I was exposed to different practices and ceremonies—potlatches and events like that, which have greatly inspired my work,” she says.

Guná’s artistic journey began when she was 12 years old, close to the time her mother decided to form the Dakhká Khwáan Dancers, an Inland Tlingit dance group. One of her mother’s major influences in starting the dance group was her own mother, Guná’s grandmother, Doris Mclean (who also held the name Guná).

Guná describes her grandmother as a trailblazer who advocated for her people “to be proud of who we are and what our ancestors left behind for us.”

“My mother rekindled that spirit by starting the dance group,” Guná says. “I remember, at the age of 12, watching this dance group ‘perform’—for lack of a better word—for a mostly Indigenous audience. And while some of the audience was dealing with stress and sadness that day, you could see the pride on their faces when that dance group came in.

She notes that she also felt incredible pride while watching the dancers and that the experience was akin to an awakening.

“I felt something come alive within me that day, something that had been asleep my entire life,” Guná recalls.

Now 29 years old, Guná has come a long way since that fateful day of dance.

If you live in Whitehorse or elsewhere in the Yukon, there is a reasonably good chance you’ve caught a glimpse of her formline work. (‘Formline,’ or Northwest Coast Two-Dimensional Design, is a unique design system developed over thousands of years by the First Nations of the Northern Northwest Coast. Unique shapes are used within a strict system of construction to create abstract images of animals, people, and supernatural beings that are often the owned crests of the Northern Northwest Coast nations.)

Her artwork has been displayed at numerous prominent venues within the territory, including in Whitehorse at the Yukon Arts Centre and the Yukon Literacy Coalition’s Front Street space.

Guná also created the popular ‘Consent is Sacred’ shirt, printed by the Juneau, Alaska-based Black and White Raven Company. Most recently, she completed an 18-metre-long mural on the side of the Yukon Association of Education Professionals building this past summer.

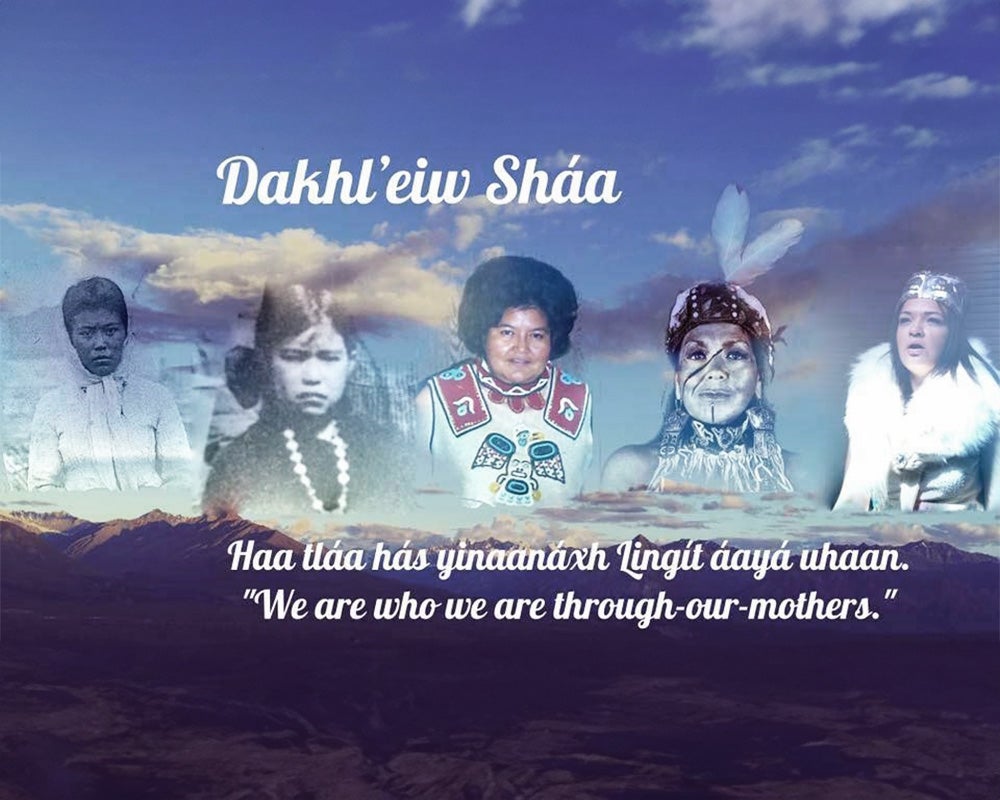

Guná’s matriarchal lineage (L-R): Great Great Grandmother Clara, Great Grandmother Agnes Johns, Grandmother Doris Mclean, Mother Marilyn Jensen and Guná Jensen

Carrying the torch

Guná is quick to acknowledge the people who inspired and mentored her on the road to becoming an artist and cultural advocate. Unsurprisingly, her mother and grandmother are the first inspirations she mentions.

“In the context of being an artist, my grandmother is a huge inspiration. She was a visionary, and I really want to recognize her, along with my mum,” she says, adding that the matrilineal strength of her family continually astounds her.

“I often feel a lot of pressure—in a good way—to carry forward that strength and to be a source of strength for my community.”

She holds the celebrated Yukon carver William Callaghan in exceptionally high regard.

William, who was part of her mother’s dance troupe, pursued an artistic education at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. Throughout his illustrious career, William created gorgeous totem poles, masks, bowls, paddles, and other carvings. In 2007, several of his pieces were temporarily displayed at the United Nations building in New York City.

Guná says that seeing William succeed in the art world made her believe that she could do the same.

“I said to myself, if Will can do it, maybe I can do it too. He’s the big reason I went to art school,” she says.

She also nods to several other incredible Northwest Coast artists who’ve inspired her, including Chloey Cavanaugh, the owner of Black and White Raven Company, Alison Bremner, and Crystal Worl.

Finally, Guná acknowledges her ancestors, who she turns to in times of difficulty.

“I’ve been taught since I was young that I can reach out to my ancestors for assistance when I don’t feel like I can find support in this physical world. That’s something no one can take away from me. No colonial structure, no horrible experience can ever take that away from me,” she says.

Guná’s ancestors would surely recognize and approve of the art she makes today. Formline is an ancient art form common to many cultures along the Northwest Coast of North America, and it is an artistic heritage proudly displayed in Guná’s works.

“I am a Northwest Coast artist because I’m carrying forward the art forms of my ancestors—formline—which has been developing for hundreds of years,” she says, adding that she has been trained in formline by numerous teachers for over a decade.

“The birth of my practice is firmly rooted in formline, and since my artistic beginnings, my practice has expanded but always utilizes formline in my different capacities.”

Guná has employed formline in many mediums, from canvas oil paintings to murals to T-shirts, and to carry very different messages, including stories of creation, struggle, reconciliation, and love. She has also used the art style to deconstruct colonial narratives.

Her formline journey was not without challenges, though. Guná says that in university, her desire to explore formline in new mediums and narratives wasn’t always accepted and was sometimes disapproved of by her instructors and peers.

Still, she overcame this ignorance and has soared in her embrace of formline. In that regard, it could be argued that Guná’s journey with formline mirrors the history of the art style itself, which was suppressed by colonizers in the 18th century.

Like the art style she loves, Guná overcame this opposition and is today a proud torchbearer for her ancestors’ artistic heritage.

Powerful art for a profound day

This past summer, Guná found time in her busy schedule to create the stunning art featured on the 2024 Orange Shirt that Northwestel is gifting to employees across our operating area for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, a day to honour the children who never returned home and the survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities.

The Orange Shirt’s design is a vivid blend of blue and white formline that depict a small being nestled lovingly in two hands. The two hands, Guná notes, represent a caring protector and form a subtle heart shape.

“This design kept coming to me. The child, or little being, is cuddled up and curled up—but not in an uncomfortable way—in the safety of two hands. These hands represent our protecting power,” she notes of the art.

It’s not the first Orange Shirt design Guná has created. She says she designed one in the late 2010s but hasn’t since due to her concerns about themes as big as truth and reconciliation being reduced to a single date on the calendar.

“I’ll be really honest: I struggle with the idea of a single day being put on something as profound as truth and reconciliation and the themes, stories, and experiences that are still so heartbreaking and still permeate our communities,” she tells us.

“I’ve borne witness to a lot of this pain throughout my life.”

However, after ground-penetrating radar discovered 15 potential grave sites at the former Chooutla Indian Residential School in her hometown of Carcross last year, she began pondering the idea of designing another Orange Shirt.

“And then Northwestel reached out to inquire about my interest in designing an Orange Shirt for them, which really gave me the incentive to do it. Receiving support with having the shirts made and the designs printed really gave me the support I needed to focus on the design work itself,” Guná says.

“I also wanted to create a design to be a part of that day again, to provide a more current representation of my relationship with this day and my perspectives on it. It was also a chance to provide a more accurate representation of my artwork on an Orange Shirt, because my artwork has changed a lot since the last time I did one,” she adds.

Speaking about her latest Orange Shirt artwork, Guná is clearly incredibly proud of her design and its meaning—particularly in light of recent discoveries at former residential school sites.

“This shirt recognizes the children that have never been recognized and have never been found, which is painfully correlated to what’s happening in my own home.”

“At the centre of the design is a young being. This little being is a child being cuddled gently, surrounded by protection. This protection is translated through the two turquoise hands surrounding the child. These hands represent a being from the supernatural world, for me they represent Haa Shagoon. It represents all the spirits of the sacred natural world, holding this child with infinite love. They hold this child and carry them through their journey every step of the way. The child is protected, and the child is loved”– Guná

Art and culture, reconciliation and truth

“I don’t think you can make art without there being a reason for it or some kind of influence, and I think influence is completely tied to culture,” Guná says matter-of-factly in response to a question about the connection between art and culture.

She shared a quote she first heard in a lecture by artist David Robert Boxley of Metlakatla, Alaska. Boxley states, “Formline is our culture in two-dimensional form.”

“What this means, is that formline represents the balance structures in our clan systems and politics, but it’s also a language. Unfortunately, I think that the way that Northwest Coast art was intended to communicate with the public has been lost due to our history of colonialism. It still exists in our own communities, but not with Canadian society.”

In speaking with Guná, it’s apparent that she views her art and culture as intrinsically connected. But she also quickly points out that art is a poignant method of transmitting ideas. For example, she notes that the image she crafted for Northwestel’s 2024 Orange Shirt was designed to communicate a specific message and that she took considerable time to think about the best way to communicate that message visually.

“The message is that our protecting power is holding our people, that there is divine justice in the world and that this divine justice will do its job—it will take care of things,” she says, adding, “I also hope when Indigenous people from different communities—from their different families, when they look at the shirt, they feel seen and recognized, but most importantly, loved and held.”

When asked whether art can be used as a vehicle for reconciliation between Indigenous cultures and the broader cultural tapestry that now exists across Turtle Island, Guná says she doesn’t have a clear-cut answer—it’s simply too big of a question. However, she expresses confidence that art can be a powerful influence in healing and a gateway to deeper meaning.

She tells us that art has always been at the epicentre of culture and has, since the dawn of humanity, been able to move and mould viewers—and the course of history—in unexpected ways.

“Art has this ability to provide layers, and it can gently guide a viewer into diving deeper into concepts and themes that can be not so easy to talk about,” Guná says.

She notes that truth is difficult for many people to discuss and accept. While reconciliation is perhaps the word that gets the most attention on National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the establishment and acceptance of truth are essential to progress in reconciliation.

“It’s really uncomfortable to stand in truth, and I think that, in a lot of spaces, people aren’t ready to stand in that truth,” she says.

Hopefully, through her art, Guná will help us all to face the discomfort and find the courage to stand in truth.

***

Thank you, Guná, on behalf of the entire Northwestel team for contributing your artwork for the Orange Shirts our employees will wear this year. We look forward to following your artistic adventures in the years to come! (You, too, can follow Guná on Instagram at @gunadesigns)

Click here to view the incredible artwork that adorned the Northwestel team’s Orange Shirts in previous years.

Northwestel is committed to following the path of Truth and Reconciliation. We serve 97 communities, each on the traditional territories of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. We are grateful for the many Indigenous partnerships over 40 years that have helped build a strong northern network.

If you’d like to learn more about what Northwestel is doing to advance reconciliation in our workplaces and the communities we serve, check out ‘Our Path Forward,’ our team’s 2023 progress report on reconciliation.

If you are a residential school survivor or know someone seeking support, please visit www.hopeforwellness.ca to call, chat online, or find additional resources.

Photo credit: Zoya Lynch